With the involvement of Hungarian researchers, two previously unknown terrestrial snail species dating back 99 million years have been identified – a discovery that made international headlines in early January. The finds originate from Myanmar’s Hukawng Valley, a remote region in Southeast Asia renowned for its Burmese amber, which formed during the Cretaceous period. Known as burmite – a name derived from the country’s former name, Burma – this amber is considered one of the most fossil-rich amber deposits in the world. Over the decades, it has yielded hundreds of remarkable plant and animal fossils, including spiders, insects, amphibians, and even dinosaur remains preserved within the ancient amber.

Photo: Ádám Kovács-Jerney

Two newly identified snail species

Scientists have previously documented 30 snail species preserved in burmite. This list has now been expanded by two newly identified ancient snail species, one of which was identified with major contributions from two researchers at the University of Szeged, Ákos Kukovecz and Imre Szenti.

Photo: Ádám Kovács-Jerney

The research was carried out as part of an international collaboration. The Szeged-based researchers worked under the leadership of Jean-Michael Bichain, a researcher at the Natural History Museum of Colmar in France, alongside Barna Páll-Gergely from the HUN-REN Centre for Agricultural Research and Szent István University, and Márton Szabó from the Department of Paleontology at Eötvös Loránd University’s Faculty of Science and the Hungarian Natural History Museum.

Following high-resolution micro-CT scanning at the University of Szeged’s Faculty of Science and Informatics, the holotype of Euthema torokzselenszkyi was transferred to the Paleontological and Geological Collection of the Hungarian Natural History Museum in Budapest, where it has since become part of the institution’s permanent collection.

The cutting-edge instrument behind the discovery

As Dr. Ákos Kukovecz recalled, the collaboration behind the discovery spans many years. The joint research effort began in 2017, when the Department of Applied and Environmental Chemistry at the University of Szeged installed its first high-resolution CT system. Since then, the University has further strengthened its imaging capabilities with two additional devices, steadily expanding its capacity for advanced structural analysis.

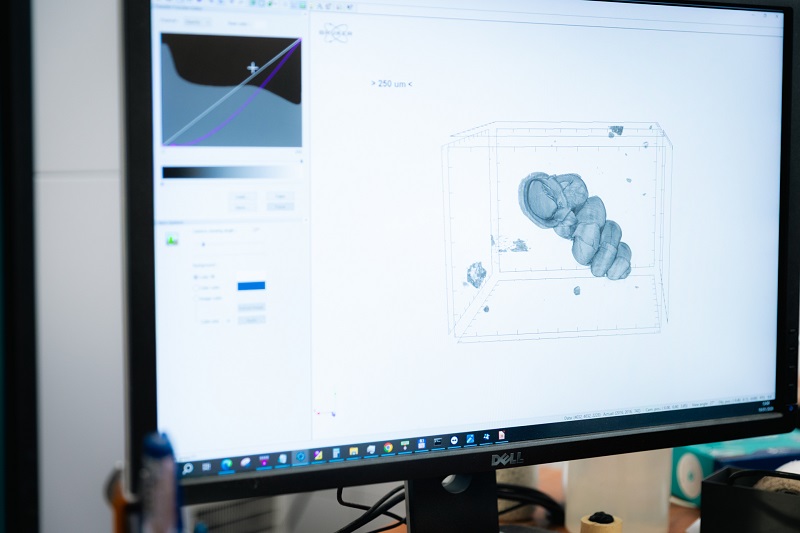

At the heart of this development is the Bruker SkyScan 2211 micro-CT, a state-of-the-art instrument capable of achieving submicrometer resolution. As the first CT system in Hungary able to operate at submicron precision, it enables exceptionally detailed examinations – even of extremely small and delicate samples – opening new possibilities across materials science and beyond.

The Bruker SkyScan 2211 micro-CT system at the University of Szeged. Photo: Ádám Kovács‑Jerney

The instrument’s primary function is to support research in chemistry, physics, engineering, and the biological sciences, but its versatility extends far beyond these core fields. The micro-CT also plays a significant role in advancing life sciences and dental research, and it has proven equally valuable in archaeological investigations.

From the outset, researchers at the University of Szeged have been committed to making the system’s capabilities accessible not only within the institution but also to scientists across Hungary. By opening the instrument to collaborators nationwide, they have ensured that its full potential benefits the broader research community.

From dinosaurs to snails

As the researchers explained, the current collaboration builds on an earlier partnership. Their joint work with colleagues at Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE) began when Attila Ősi, head of ELTE’s Department of Paleontology and one of Hungary’s most renowned paleontologists, invited the Szeged team to use micro-CT imaging to reconstruct the dentition of a dinosaur from its fossilized jawbone.

The collaboration soon expanded when Márton Szabó, also a researcher at ELTE’s Department of Paleontology, approached the Szeged scientists with a new challenge: to examine 99-million-year-old amber specimens containing tiny fossilized creatures, including spiders, cockroaches, and wasps, preserved for millions of years.

Dr. Imre Szenti. Photo: Ádám Kovács-Jerney

“Previously, this type of material was extremely difficult to study using other techniques. Although inclusions can be observed with light microscopy, this requires the organisms to be positioned very favorably within the amber – otherwise they remain invisible. In this respect, the greatest advantage of CT, or computed tomography, is that it allows us to examine what is hidden inside the amber in a non-destructive way. Using this method, we can reconstruct the structure of the animal preserved in the burmite in three dimensions. This enables specialists to accurately characterize the finds, as demonstrated in earlier studies involving click beetles, wasps, dinosaur jawbones, and, most recently, snails. Our current project is part of a longer research trajectory: after studying dinosaurs, then wasps and cockroaches, we have now turned our attention to a snail preserved in Burmese amber,” explained Imre Szenti.

Discovering something new through collaboration

As the researchers emphasized, identifying a new species is not only a matter of expertise – it also involves a measure of luck. At first glance, a specimen may seem indistinguishable from species already known to science. A snail shell, for instance, might appear identical to familiar forms, and an insect may look entirely ordinary. It is only through closer examination – often with the aid of high-resolution imaging – that subtle but decisive differences come to light.

Sometimes the distinction comes down to the smallest detail: a species may typically display three grooves, while the specimen under investigation has four. “It is precisely these subtle differences that determine whether we are looking at a new species or simply some natural variation within an existing one,” explained Ákos Kukovecz. “This is why our work is so important for our colleagues in biology. The micro-CT system provides powerful support for the non-destructive examination of paleontological finds, allowing us to reveal structures that would otherwise remain hidden.”

Dr. Ákos Kukovecz. Photo: Ádám Kovács-Jerney

The researcher also emphasized that the project’s greatest strength lies in its interdisciplinary character, where the combined expertise and methodologies of multiple scientific fields are brought together to produce meaningful results.

“No one could carry out a project like this alone,” said Ákos Kukovecz. “That is exactly what makes it such a powerful example of collaboration between universities and research groups. By working together, we are able to create something that none of us could achieve individually.”

Understanding what makes a species thrive

The current research has the potential to help biologists bridge evolutionary gaps and gain deeper insight into how life on Earth evolved – including the crucial transition from aquatic to terrestrial environments.

“When researchers from other fields come to us and we see that spark – that genuine drive to discover – even if the topic lies outside our core focus, we are always open to collaboration,” said Imre Szenti. “If someone is truly enthusiastic, believes in their work, and is willing to invest the effort, we are glad to join forces. And these projects are mutually enriching; we learn from them as well, and they also strengthen the reputation of our University.”

As the head of the Institute explained, the very fact that certain ancient animals have survived in fossil form helps scientists understand which morphological traits proved evolutionarily successful. Species that thrived in their time endured long enough to leave traces behind, while less successful forms disappeared more quickly and therefore had a far smaller chance of being preserved and then discovered.

Dr. Imre Szenti. Photo: Ádám Kovács-Jerney

Where innovation meets methodology

To support their interdisciplinary work, the team operates within an exceptionally wide network of collaborations, partnering closely with dentists, energy specialists, engineers, and industrial stakeholders. Their activities span both applied and fundamental research, together defining the core profile of the materials science CT capacity at the Institute of Chemistry of the University of Szeged.

“Our approach to method development is unique at the national level, particularly in the advancement of computational techniques, with a strong emphasis on operando measurements,” said Ákos Kukovecz, head of the Institute. “In practice, this means that measurements are carried out not before or after a reaction, but in real time – under actual operating conditions. This expertise also forms the backbone of the successful energy research conducted at the University of Szeged.”

Ákos Kukovecz pointed out that supporting research across the University is a central mission of the team. “It is widely recognized that we have strong capabilities in energy research and carbon dioxide conversion. A good example is the Energy Innovation Test Station operating at the University of Szeged Science Park under the leadership of Csaba Janáky.”

The head of the Institute of Chemistry added that CT investigations serve as a key driver behind many of the team’s research initiatives. In particular, the technique has also been applied to lithium-ion batteries, with the group performing scans during both charging and discharging cycles. As reported in a study published last year, the speed of the method allowed researchers to capture as many as seven or eight complete three-dimensional images within a single charging cycle of roughly 30 minutes. This made it possible to monitor, in real time, the processes unfolding inside the battery during operation, offering unprecedented insight into its internal dynamics.

Dr. Ákos Kukovecz. Photo: Ádám Kovács-Jerney

“These types of investigations are essential to understanding how batteries truly function – how much stress they can withstand and how long they can reliably operate,” Ákos Kukovecz said. “Ultimately, this knowledge enables us to design more durable and dependable energy systems.”

The research group’s own developments are built around this same philosophy. Their work centers on operando measurements, in which CT imaging is performed while processes are actively unfolding inside the system. Whether fluids are flowing, chemical reactions are occurring, or materials are melting and transforming, the evolving three-dimensional structures can be observed and analyzed in real time.

Helping uncover ancient wasps

The versatility of the micro-CT system had already been proven in numerous studies long before the discovery of the ancient snails. In one such project, researchers examined the internal wall structure of ceramic vessels to uncover how they had been made. As Ákos Kukovecz explained, pottery can be produced using a variety of techniques: wheel throwing, coil building – where clay is shaped into rope-like strands – or hand-building from a single solid lump, formed through pressing or hollowing. Yet from external appearance alone, it is often impossible to determine which method was used to create a particular artifact.

However, the internal structure of a vessel reveals important differences. Whether it was shaped on a potter’s wheel or constructed by hand using techniques such as coil building leaves distinct structural patterns beneath the surface. “By combining CT imaging with other analytical methods, we can determine the manufacturing technique with a high degree of confidence,” explained the head of the Institute of Chemistry.

These investigations were carried out by the Szeged-based team in collaboration with researchers from the HUN-REN Hungarian Research Network (formerly Eötvös Loránd Research Network) and Eötvös Loránd University, allowing CT data to be complemented with neutron tomography measurements for even greater analytical precision.

Dr. Imre Szenti and Dr. Ákos Kukovecz. Photo: Ádám Kovács-Jerney

Imre Szenti noted that long before the research on ancient snails, the team had already achieved significant breakthroughs in paleontology. In collaboration with colleagues at Eötvös Loránd University, they identified three previously unknown ancient wasp species based on detailed three-dimensional models generated using the micro-CT system. The approximately 85-million-year-old specimens were discovered in amber from the city of Ajka in Hungary. One of the newly described species was named after the Hungarian rock band 30Y, another in honor of the grandfather of one of the discoverers, and the third after the geologist Miklós Soós.

“In the case of the wasps, the wings and legs were crucial for identifying the new species,” Dr. Szenti explained. “By rotating the specimens using CT, we were able to examine the antennae and the fine structural details of the legs. It was through this close analysis that we recognized we were dealing with species previously unknown to science.”

Precision at the microscopic level

Imre Szenti emphasized that this kind of close analysis is exactly where micro-CT offers a major advantage over light microscopy: the specimen can be rotated and examined from every angle, and researchers can zoom in on exceptionally fine structural details without physically manipulating the sample. In addition, CT analysis enables precise parameterization, allowing the dimensions of the examined specimens to be measured quantitatively and with high accuracy.

Just as specific features of a snail shell – such as the curvature or diameter of a whorl – can be measured with precision, the same imaging data also make it possible to quantify internal structures. By contrast, such measurements are far more challenging under a microscope, where perspective and sample orientation can significantly affect the results. CT measurements, on the other hand, are performed at the pixel level, allowing highly accurate quantitative data to be derived, because the real-world dimensions represented by each pixel are precisely known. In materials science, the resolution of CT measurements done in Szeged depends on the sample and the imaging configuration, but a precision of at least 100 micrometers – one-tenth of a millimeter – is routinely attainable. However, in many cases, the resolution is significantly higher and can even reach below 10 micrometers, the researchers added.

Dr. Ákos Kukovecz. Photo: Ádám Kovács-Jerney

“Researchers rarely come to us with tasks that fall comfortably within standard parameters,” Ákos Kukovecz said. “More often, they bring challenges that push beyond routine procedures – cases where it is not enough to simply place a sample into the instrument and press a button. Instead, we have to work intensively to extract the right information while operating at the very limits of the system’s capabilities. None of this would be possible without the dedication and expertise of the highly skilled researchers here at the University of Szeged,” he emphasized.

Promising developments ahead

Ákos Kukovecz noted that energy-related materials science will continue to define the core direction of their research. This includes the study of catalysts and catalytic systems, reactor cells, and the structure and operation of energy storage devices such as batteries.

A further key priority is the continued advancement of operando methods. In this area, the team is working to integrate sample holders and complete experimental systems directly into the CT instrument, enabling a wide range of processes to be monitored in real time with exceptional precision.

Dr. Imre Szenti. Photo: Ádám Kovács-Jerney

Alongside the team’s CT research, a major priority this year is making full use of the cryo-electron microscopy center soon to begin operation at the University of Szeged. The new facility marks a significant milestone for cryo-EM research in Hungary and will provide advanced imaging capabilities for life sciences and materials science projects not only at the University, but also for research institutions across the country and the wider region. In this next chapter of imaging-driven innovation, Imre Szenti is set to play a central role.

At the same time, collaborations in archaeology will continue to expand. The Szeged-based team is therefore poised to contribute to further discoveries – revealing new insights into ancient life and deepening our understanding of the past and the evolutionary paths that shaped the world we inhabit today.

Original Hungarian article by Tímea Fülöp

Feature photo: Dr. Imre Szenti and Dr. Ákos Kukovecz. Photo by Ádám Kovács-Jerney