Investigations into land use practices of the ancient Maya, the historical evolution of rivers in the Carpathian Basin, and the authenticity of ancient artworks – these are just a few examples of the research made possible by the advanced geochronology laboratory at the University of Szeged. With its cutting-edge infrastructure, the laboratory enables researchers and students to conduct complex age determination analyses on samples dating back hundreds of thousands of years. Now, this state-of-the-art facility has contributed to a scientific breakthrough: researchers have uncovered geological evidence suggesting that, over the past three centuries, multiple tsunamis may have struck the western coast of the Black Sea. As in previous projects, the laboratory’s sediment analysis and precise age determination techniques provided the crucial clues.

Researchers at the geochronology laboratory at the University of Szeged’s Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences have uncovered geological evidence indicating that the western coast of the Black Sea may have experienced several tsunamis in the past three hundred years. This marks another breakthrough for the facility, which is made up of several specialized units and employs two primary methods. Its unique strength comes from the combination of radiocarbon analysis, used to date organic materials, and luminescence analysis, which helps determine the age of sediments, including inorganic deposits.

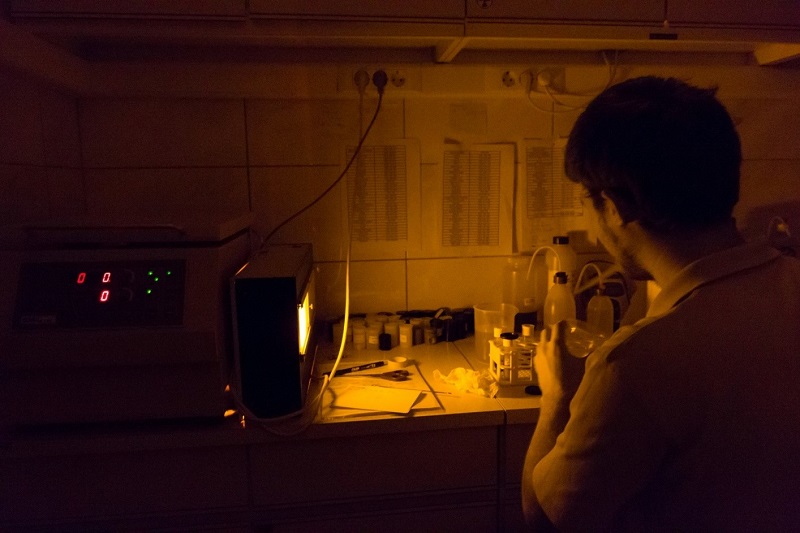

To prevent any exposure to light, most of the work is carried out by lab staff under carefully controlled darkroom conditions.

Photo: University of Szeged, Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences

“The luminescence method allows us to determine how much radiation sediment grains have absorbed from their environment since they were buried. This is made possible by the fact that natural environments are full of radioactive isotopes, and the radiation they emit gradually alters the crystal structure of the mineral grains we study – a process that continues over time. Using specialized instruments, we can measure these changes after the fact by detecting how many electrons were excited and then trapped by radiation. From this, we calculate the absorbed dose. Ultimately, this method reveals when the grains were last exposed to sunlight, as light resets their internal ‘clock,’” explains Dr. György Sipos, head of the Department of Physical and Environmental Geography at the University of Szeged. Importantly, in addition to conducting such advanced research, the geochronology laboratory at the University of Szeged also plays a vital role in connecting Hungarian researchers with international projects.

Dr. György Sipos: Age determination research is supported by cutting-edge technology at the University of Szeged’s Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences.

Photo: Ádám Kovács-Jerney

Tsunamis have the potential to cause catastrophic destruction. One of the most devastating seismic sea waves in recorded history struck Southeast Asia 20 years ago, claiming more than 230,000 lives across Indonesia, Thailand, and several neighboring countries. These powerful waves are most often triggered by earthquakes or underwater landslides.

While the Black Sea has likely never experienced tsunamis on such a catastrophic scale, smaller ones may have occurred in the past. Recognizing this potential risk, researchers at the University of Bucharest have launched a project to assess the region’s tsunami threat. This research is especially important given the ongoing population growth and expanding coastal development along Romania’s Black Sea coast.

The sediment samples were collected by Romanian researchers and analyzed by the Hungarian team.

Photo: University of Bucharest

“Our Romanian colleagues collected the tsunami sediments from natural depressions located several hundred meters inland and approximately eight meters above present sea level, near the popular resort town of Mangalia. Measurements conducted in Szeged indicate that the age data align closely with the earthquakes of 1794 and 1901. While historical records confirm that the 1901 earthquake triggered a tsunami, no such documentation exists for 1794. Our findings will help reconstruct what happened during that earlier event,” explains Dr. György Sipos.

Thanks to their specialized laboratory facilities, researchers in Szeged have contributed to numerous international collaborations. As part of these projects, they have investigated ancient Maya agricultural practices in the lowlands of Guatemala. In addition, they are set to publish a paper – co-authored with French and German researchers – analyzing sediment samples collected from several oases in the United Arab Emirates. Their research focuses on identifying periods of increased rainfall in the Rub’ al Khali, the world’s largest continuous sand desert.

The research on Black Sea tsunami sediments is part of the PNRR-III-C9_2022-I8-CF253 (ChronoCaRP) project. Moving forward, however, the research group plans to extend its investigations to the eastern basin of the Mediterranean. Sample collection is scheduled to begin this spring in the Aegean Sea region.

Recognizing the significance of tsunamis as a natural hazard, the team will present their findings at an international conference on natural hazards and climate change, which will take place in Szeged at the end of May.

Original Hungarian text by Ferenc Lévai

Feature photo: pexels.com

Article photos:

Ádám Kovács-Jerney; University of Szeged, Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences;

University of Bucharest